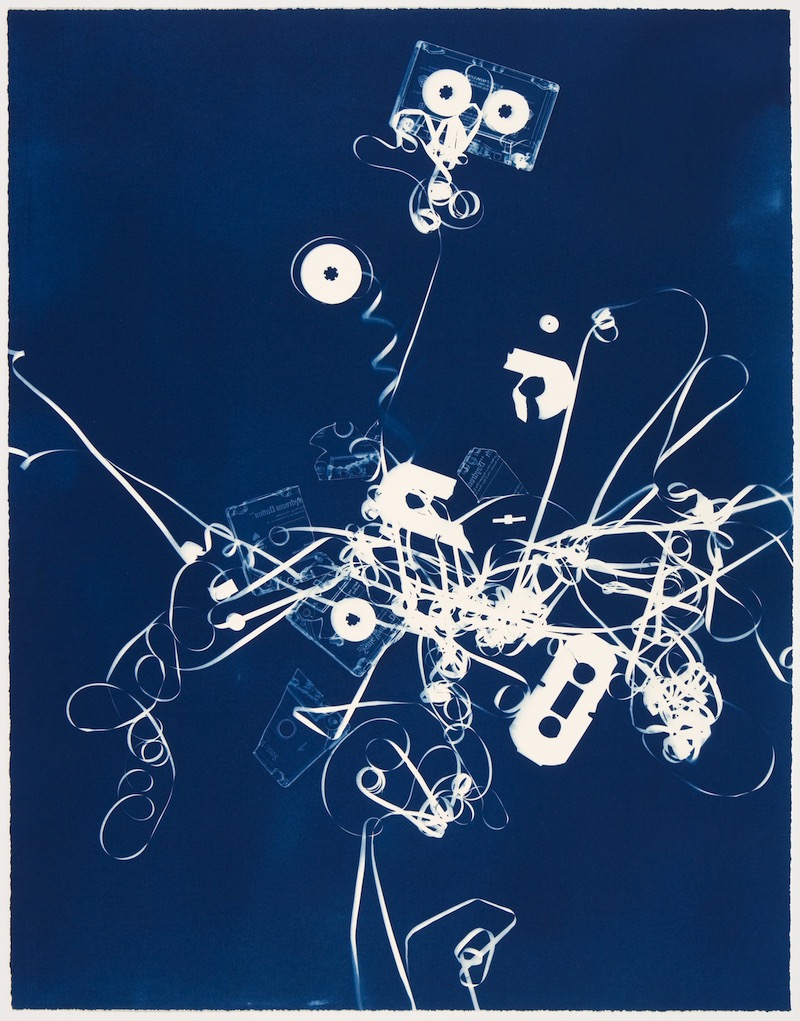

When I was in the sixth grade, I was in a Vic-20 user’s group. I had a revved-up Commodore Vic-20 with an 8k-expansion cartridge and an external tape drive. Though floppy discs were available, we traded games and software via cassette tapes. There was this device at every meeting called “The Octopus.” It was a port replicator, and when we all plugged in our tape drives for copying multiple programs at once, it looked like a giant, electronic octopus.

Looking back at its long reign, the cassette tape is a strange piece of technology. It was horrible for software storage and retrieval. Indexing more than one program on a tape was nearly impossible. The only way to tell where one ended and the next started was by keeping note on the numbers of an unreliable analog counter. At least with music you could hear where the next song started.

The cassette tape, which was cued up in the 1960s to challenge the LP and the 8-track market as the musical format of choice, didn’t take off until it became hyper-mobile in 1979 thanks to the personal, portability of the Sony Walkman. High quality sound as such once required equipment too cumbersome to be carried. The cassette in concert with the Walkman gave everyone their own soundtrack. Their portability and customizability made them the personal electronic item. “The other big advantage of cassettes, of course, was that they were recordable,” Steven Levy elaborates, in an essay celebrating the thirty-year anniversary of the Walkman:

You’d buy blank 90-minute cassettes (chrome high bias, if you were an audio nut) and tape one album on each side. (Since most records were shorter than 45 minutes, you’d grab a song or two from another album to avoid a long dead spot before the tape reversed.) And you’d borrow albums from friends and tape your own. You could also tape from other cassettes, but the quality degraded each time you made a copy made from a copy. It was like an organic form of DRM. Everybody had a box with hand-labeled cassettes and before you went on a car trip, you’d dig in the box to find the tunes that would soundtrack your journey.

The magnetic tape was as much a part of the journey as the road. The portability and recordability of cassettes, of which all sounds so very labor-intensive now, made them the precursor to MP3s and iPods and today’s mobile streaming. Personal media, as opposed to mass media, may have been birthed by the book, but the cassette took it to a new level. Just as the book individualized the exchange of stories and information, the cassette tape and its attendant technologies individualized music listening. When the Walkman first came out, it was intended for sharing. The first models released had two headphone jacks. I distinctly remember the first one I listened to having dual jacks. Nevertheless, initial sales numbers indicated that few users were sharing their devices, so Sony retooled its approach. In the ads, Alex Weheliye writes that “couples riding tandem bicycles and sharing one Walkman were replaced by images of isolated figures ensnared in their private world of sound.” As William Gibson puts it,

The tape recorder was the first widely available instrument that allows you to manipulate media. I remember I bought the first Walkman I ever saw… I didn’t even have a tape recorder. I had to go and get someone to make me a tape. The experience of taking the music of your choice and being able to move it through the environment of your choice had just never been available. It felt weirdly subversive. I could walk through rush hour crowds listening to Joy Division at skull-shattering volumes (laughs)… Like you were having this completely different experience that was completely altering the way it all looked, and no one knew.

This source of secret sound, the black box of the personal stereo, is where its cultural meaning truly lies. “People who walk around with a Walkman might seem to signify a void, the emptiness of metropolitan life,” writes Iain Chambers, “but that little black object can also be understood as a pregnant zero, as the link in an urban strategy, a semiotic shifter, the crucial digit in a particular organization of sense.” Where the television brought mass-produced narratives into our home, conflating public and private in its own way, the Walkman allowed us to create our own private narratives in public.

The ubiquity of the cassette tape marked the shift from home recording to personal drift, as well as the loosening of the corporate grip on copyright and the individual’s perceived right to copy. “The tape cassette is a liberating force…” Malcolm McLaren proclaimed in the early 1980s. “Taping has produced a new lifestyle.” Long before CD burners became standard equipment on the personal computer and MP3s and streaming liberated music from physical formats altogether, cassettes made recording and customization possible. The formalized mix tape, in McLaren’s words, “allowed for the kinds of communication ultimately threatening to power.”

“Home taping is killing music,” proclaimed the British Phonographic Industry. It sounds rather quaint now, but the British Phonographic Industry—BPI, the English sister of the RIAA—was incensed. Their attitude was that every blank tape sold was a record stolen. “BPI says that home taping costs the industry £228 billion a year in lost revenue,” McLaren said in 1979, “so they’re not happy that Bow Wow Wow have already reached No. 25 on the singles chart… ” The home-taping controversy was custom-made for McLaren. He was managing Bow Wow Wow who had a hit with a song celebrating home taping called “C-30! C-60! C-90! Go!” The numbers refer to the standard lengths of blank cassettes: 30-, 60-, and 90-minute formats. “In fact,” adds McLaren, “it’s the classic story of the 80s. It’s about a girl who finds it cheaper and easier to tape her favorite discs off the radio… which is why the record companies are so petrified.” “Mix tapes,” adds Ball, “as community-based, localized mechanisms of distribution, pose a threat to the process of managing the flow of ideas…” which in the recording industry’s opinion was strictly the business of the RIAA.

In the decades since, the industry’s paranoia has only increased. Once music was converted to digital files, then compressed to sizes tradable by computers via phone lines, listening to music on a physical format of any sort was doomed. Sony ceased production of the cassette edition of the Walkman on October 25, 2010, but the internet, which has been feeding music to portable players since the late 1990s, continues the path of both personal media and the piracy thereof.

Bibliography:

Ball, Jared, I Mix What I Like: A Mixtape Manifesto. Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011, p. 125.

Bromberg, Craig, The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren. New York: HarperCollins, 1989.

Chambers, Iain. Migrancy, Culture, Identity. New York: Routledge., 1994, p. 49-50.

Du Gay, P., Hall, S., Janes, L., & Negus, K, Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. London: Sage, 1997.

Eshun, Kodwo, The Co-Evolution of Humans and Technology: A Discussion with William Gibson. In Roy Christopher (Ed.), Follow for Now, Volume 2: More Interviews with Friends and Heroes. Santa Barbara, CA: Punctum Books, forthcoming, Winter 2021.

Hagood, Mack, Hush: Media and Sonic Self-Control. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019, p. 195.

Levy, Steven. “The Blank Generation: 1979 as Audio Cassette Enabler.” Gizmodo, July 15, 2009.

McMahon, Jr., C. J. & Graham, Jr., C. D. Introduction to Engineering Materials: The Bicycle and the Walkman. Philadelphia, PA: Merion Books,1992.

Rasmussen, Terje, Personal Media and Everyday Life, Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2014.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, p. 135.