Once exclusively a fan phenomenon, internet memes have become a mainstay in marketing. Not long ago, they were the domain of crafty internet users bent on making and spreading bite-sized cultural commentary. In his recent Complex article, How Memes Changed the Rap Game, Andre Gee quotes one marketing and advertising agency saying that “meme marketing allows potential new fans to discover new music without feeling like they’re being advertised to.”

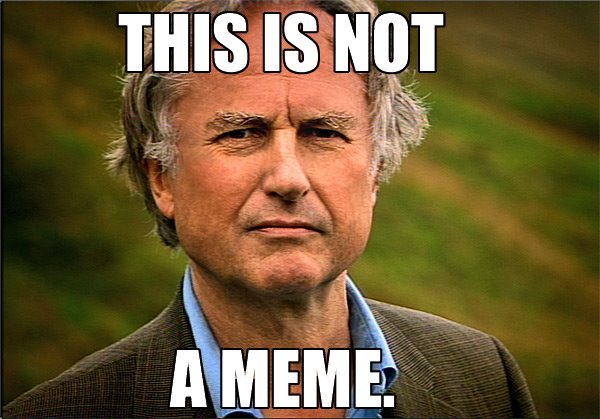

As originally conceived by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, a meme is “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation.” It is the smallest spreadable bit or iteration of an idea. Memes are based on genes, Dawkins’ original analogy contends. He writes,

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.

Others have taken the idea, the “meme” meme, further. Kate Distin has perhaps taken up the idea most earnestly with two books, The Selfish Meme (2005) and Cultural Evolution (2011), the latter of which moved away from memes and looked closer at languages, written, spoken, and musical. In her book The Meme Machine (1999), Susan Blackmore distinguishes between memes that copy a product and memes that copy instructions. Similarly, in The Electric Meme (2002), Robert Aunger extends the meme metaphor by adding phenotypes and conflating them with artifacts. With Memes in Digital Culture (2013), Limor Shifman does a noble job attempting to reconcile Dawkinsian memes with internet memes.

Distinguishing imitation or replication as a process of communication, as well as integrating Everett M. Rogers’ closely related diffusion of innovations theory, Brian H. Spitzberg proposes an operational model of meme diffusion. He writes, “Communication messages such as tweets, e-mails, and digital images are by definition memes, because they are replicable transmitters of cultural meanings.”

In his book of the same name, J.M. Balkin imagines memes as bits in a “cultural software” that makes up ideologies. In Genes, Memes, Culture, and Mental Illness (2010), Hoyle Leigh writes that “a meme is a memory that is transferred or has the potential to be transferred.” There’s even The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Memes, which only discusses internet memes in one chapter of its 23, and as an afterthought (Appendix E).

Both biological and cultural evolution require competition and collaboration, and no one knows at what level the selection, transfers, and changes happen: Genes? Individuals? Groups? Where memetic theories are concerned, another major problem is one of scale. What size is a meme? Where are its borders? What do memes add up to? Like genes, germs, and viruses, Dawkins gave memes “fitness,” which means that a very “healthy” meme that grows big and strong can still be very negative and quite dangerous. As Virus of the Mind author Richard Brodie once told me, “Memetic theory tells us that repetition of a meme, regardless of whether you think you are ‘for’ it or ‘against’ it, helps it spread. It’s like the old saying ‘there’s no such thing as bad publicity.’” This is an overlooked aspect of memetics that also applies to internet memes. Think here of internet users reposting memes with which they disagree and commenting to say so. Regardless of the context, the meme still spreads. That is, even if it is presented in a negative light, the meme is fitter, healthier, and stronger as long as it spreads. Retweets might not equal endorsements, but they do strengthen the memes.

Another problem you may have noticed in the “meme” meme via the brief and selective literature review above is that the genetic analogy is not universal. Some theorists prefer an analogy with viruses. As many aspects as they might share as useful metaphors, genes and viruses are not the same thing. Douglas Rushkoff Media Virus! (1994), Brodie’s Virus of the Mind (1995), and Aaron Lynch’s Thought Contagion (1996) all take up the virus analogy over the gene one. Maybe it’s a better model, as when something is “viral,” it spreads. When something is “genetic,” it doesn’t necessarily. Sure, genes are passed on, but viruses are inherently difficult to stop. Spreading is what they do. This epidemiological view of culture has been most thoroughly explored by anthropologist Dan Sperber. His 1996 book, Explaining Culture, goes a long way to doing just that, using a naturalistic view of its spread. Some prefer to skip the memes altogether. Malcolm Gladwell, whose 2000 bestseller, The Tipping Point, also takes an epidemiological view of culture and marketing but without ever mentioning memes, told me shortly after its release,

As for memetics, I hate that theory. I find it very unsatisfying. That idea says that ideas are like genes — that they seek to replicate themselves. But that is a dry and narrow way of looking at the spread of ideas. I prefer my idea because it captures the full social dimension of how something spreads. Epidemiologists are, after all, only partially interested in the agent being spread: They are more interested in how the agent is being spread, and who’s doing the spreading. They are fundamentally interested in the social dimension of contagion, and that social dimension — which I think is so critical — is exactly what memetics lacks.

If memes are indeed analogous to genes, then the real power of memes is that they add up to something. I’m no biologist, but genes are bits of code that become chromosomes, and chromosomes make up DNA, which then becomes organisms. Plants, animals, viruses, and all life that we know about is built from them. “The meme has done its work by assembling massive social systems, the new rulers of this earth,” writes Howard Bloom. “Together, the meme and the human superorganism have become the universe’s latest device for creating fresh forms of order.”

Perhaps that was true in the mid-1990s, when Bloom wrote that, or in the mid-1970s when Dawkins wrote The Selfish Gene, but the biases and affordances of memes’ attendant infrastructure has changed dramatically since. After all, memes have to replicate, and in order to replicate, they have to move from one mind to another via some conduit. This could be the oral culture of yore, but it’s more and more likely to be technologically enabled. Broadcast media supports one kind of memetic propagation. The internet, however, supports quite another.

Units vs Unity

How are we to understand culture through a metaphor that’s based on another metaphor? Genes are figurative as well, a rhetorical tactic deployed simply to give a name to something. Meta-metaphors are known as pataphors, and they are so useless as to be called a fake science by their originator Alfred Jarry. Pataphysics is to metaphysics what metaphysics is to physics. It’s one level up. “Pataphysics… is the science of that which is superinduced upon metaphysics,” wrote Jarry, “whether within or beyond the latter’s limitations, extending as far beyond metaphysics as the latter extends beyond physics.” He added, “Pataphysics is the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments.” If ever there were a scientific concept that proved pataphysical, it is sure to have been the meme. Virtual. An imaginary solution.

In her book, How the Gene Got Its Groove, Elizabeth Parthenia Shea writes,

As a rhetorical figure, the ‘gene’ moves from context to context, adapting to a broad range of rhetorical exigencies (from the highly technical to the intensely political to the ephemeral and the absurd), carrying with it a capacity for rhetorical work and rhetorical consequences. As the examples in this book show… the rhetorical consequences of the figure of the gene often include the assertion of boundaries, with authoritative knowledge on one side and playful language, stylistic devices, and rhetoric on the other.

Memes only work if they move. If they are units of culture then in order to build and maintain that culture, they have to move.

Memes are supposedly what makes us different from all other species in that we can deny our biological genes because of our cultural memes. As we’ve seen, memes have been touted as a unit of thoughts, belief, ideology, memory, learning, influence, and, of course, culture. As the media theorist Douglas Rushkoff told me in 1999,

I’ve been into memes off-and-on since Media Virus! (1994), and I still think they’re an interesting way to understand culture. But meme conversations spend much more time explaining memes than they accomplish. In other words, the metaphor itself seems more complex than the ideas it is meant to convey. So, I’ve abandoned the notion of memes pretty much altogether.

Even in the 1990s, the web’s salad days, the concept was so beleaguered by explanation that one of its major champions dropped the idea. Rushkoff continues,

I remember I was doing an interview about Media Virus! for some magazine, and it was taking place at Timothy Leary’s house. And he overheard me mention memes, and the journalist asking me to explain to him what ‘memes’ are. Afterwards, Timothy teased me. ‘Two years you’ve been carrying on about memes,’ he said. ‘If you still have to explain what they are every time you mention them, it means they just haven’t caught on. Drop ‘em.’

Now everyone knows what a meme is, but it’s not the thing Rushkoff was talking about in the 1990s. One is far less likely to have to explain what memes are as you are what they aren’t. An internet meme is a meme now. Ludwig Wittgenstein once said there was no such thing as a private language. The presumption being that language, the prime mover of ideas if ever there were such a thing, only works if it is shared. The same can be said of culture. It only works if it is shared. If memes never add up to anything larger than memes, the concept is dead, and so is its culture. Dawkins’ idea has been hi-jacked by the jacked-in, mimed by the marketers and spread through networks, for better or worse.

This post is an excerpt from Chapter 6 “Metaphors Be With You” of The Medium Picture (forthcoming from punctum books) and contains parts from my chapter “The Meme is Dead, Long Live the Meme” from the book Post Memes: Seizing the Memes of Production, edited by Alfie Bown and Dan Bristow (punctum books, 2019)